Introduction

We have already documented the development of a device for controlling the Tibialis Anterior leg muscles during movements such as running. The software for that device was developed in C++ for maximum performance and for portability to microcontrollers. The existing device was running on a 1GHz Raspberry Pi Zero. In the following we are going to try running the code on a microcontroller.

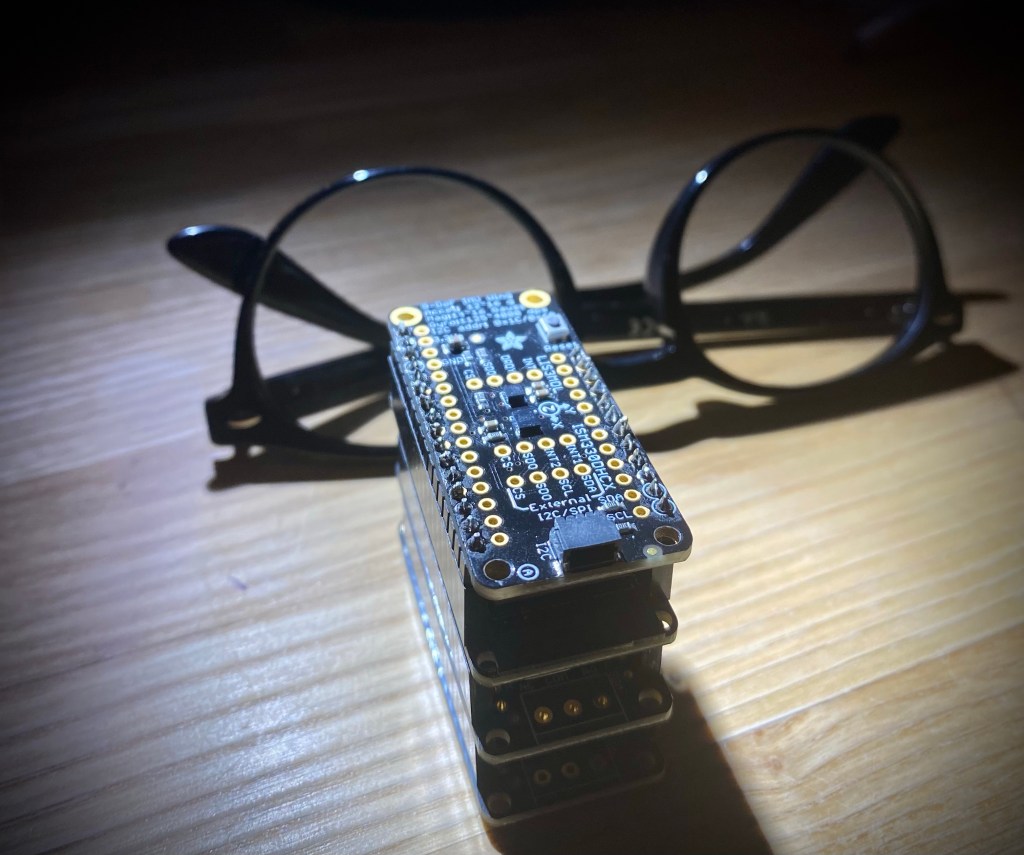

The new design is primarily based on components from Adafruit Industries, and most importantly the software is running on a Huzzah32 controller. The Feather stack dimensions at only 50x22x38 mm (excluding battery).

Refactoring

The existing code repository is based on cross platform development in Microsoft Visual Studio. As part of this effort we will transition the code into a PlatformIO project.

PlatformIO has support for unit tests and libraries. Everything should be transitioned to that layout. Also, it would be preferable if we continue the support for Raspberry Pi Zero.

Movement Translation

In the following we discuss the algorithm that translates sensor readings into movements. Given a previously demonstrated movement, we are mostly interested in knowing the progression of said movement (a value between 0 and 1).

Overall Algorithm

The software is currently configured to create models in which a movement is represented as a sequence of 100 different sensor mean vectors. In addition, the software is configured to match 50 different movement speeds, ranging from 80% to 120% the demonstrated movement speed.

In essence, the algorithm will maintain values for a 50×100 matrix for combinations of speed v and progress p given a sequence of historic observations. The algorithm asserts a constant speed but applies exponential filtering (Kalman), so that this asserting mainly applies to the most recent observations. In essence, we can achieve this by applying the progress according to the elapsed time since last observation and applying only the the probability of most recent observation given progress (more detail can be found in the code repository). Given this matrix of likelihoods over velocities and progressions, we can calculate the probability of progress.

While the complexity of the algorithm is somewhat modest, it is not certain that the processor on the microcontroller will be powerful enough to run the algorithm at the required speed. The existing hardware runs at about 100 samples per second, and we would like to demonstrate the same capability on the microcontroller.

Given a processor speed of 240MHz and a data rate of 100 samples per second, we estimate having about 2.4 million clock cycles per sample. The matrix contains 500 values, which gives us about 4800 clock cycles per value. This does not sound unrealistic, but let’s look at some actual performance figures.

Performance Testing

For this test we use the ESP timer for triggering the algorithm 100 times a second. We then use the CPU statistics feature to show us the CPU load of the various processors and tasks.

We run this test with The ESP timer configured at 500 Hz, but it is possible that this test strategy will not compute exact performance figures. But it at least should give us an indicator of processing speed.

As shown on the figure, the movement translation is run 100 times per second. The translator_task is run on core 1 and apparently consumes 22% of all available processing resources.

Since processing is currently limited to a single task, it seems relevant to notice that we are using 44% of the processing power of core 1. It therefore seems like we have plenty of compute power to spare. On a linear scale, we can increase the complexity by 127% (100/44-1) before we reach the limit of the processor. For instance, we could concurrently evaluate two different models and still stay within the limits of the processor. Or we could increase the processing rate to 200 samples per second.

Movement Learning

The existing hardware had plenty of memory and storage space, but the new hardware is somewhat limited. Storing 6 dimensional vectors at a rate of 100 samples per second for 1 minute will require 60x100x6x4 B = 144 KB. The total memory capacity of the device is only 512 KB, so a strategy of collecting data in memory for later learning might not be optimal.

It might be possible to store the data to flash storage, since the controller is equipped with a total of 4 MB flash storage. Since this storage will be used also for storing the software and for storing previously demonstrated movements, we might consider doing more compact representation. For instance, if a model consists of 100 mean values, we could simply collect samples for a single movement and immediately aggregate them. The size of a model in this representation is fixed at 100x6x4 B = 2400 B.

The current design, where the raw input data is stored, allows for a transparent transition to more complex translation models. But a change to a less memory consuming approach seems required.

Wireless Remote Control

Since I have no previous experience with Bluetooth programming, I found it a bit complicated to figure out how to make the microcontroller pair with the game pad for enabling wireless remote control.

I have had several attempts at creating the code for handling communication with the game pad, but it was not until today that I managed to make it work appropriately. It still as a few minor quirks, but these seems to go away with a reconnect, so maybe it’s good enough for now.

Status

It looks like all major uncertainties in relation to external components have now been resolved and all that is missing is enablement of movement learning with a smaller memory footprint. Maybe some progress will appear on that shortly.